NatureScot Research Report 1361 - SPANS Scotland’s People and Nature Survey 2023/24 - health and wellbeing report

Published: 2025

Authors: Duncan Stewart and Jim Eccleston (56 Degree Insight)

Cite as: Stewart, D. and Eccleston, J. 2025. SPANS Scotland’s People and Nature Survey 2023/24 - health and wellbeing report. NatureScot Research Report 1361.

What is SPANS?

Scotland’s People and Nature Survey (SPANS) is a large-scale population survey that provides detailed data on how adults in Scotland use, value, and enjoy the outdoors and connect with nature. SPANS data allow NatureScot to monitor key trends over the long-term and produce statistically robust insights.

The core research objectives for SPANS are to deliver strong quantitative evidence in relation to the following key areas:

- Visits to the outdoors for leisure and recreation;

- Recreational use of, and attitudes towards, urban greenspace;

- Connection to nature;

- Benefits of engagement with the natural environment;

- Environmental attitudes and behaviours.

Health and wellbeing report

This report provides findings from SPANS 2023/24 which covers a 12-month period from March 2023 to February 2024. The 2023/24 survey followed on from previous waves of SPANS which ran on a triennial basis between 2012 and 2019.

SPANS 2023/24 was delivered with support from our contributing partners: Scottish Forestry, Sustrans, Cairngorm National Park Authority, and Loch Lomond & the Trossachs National Park Authority.

This report focuses on findings relating to health and wellbeing from SPANS 2023/24. A suite of other reports with a focus on specific areas of interest have also been produced using data from SPANS 2023/24:

- Headline report

- Outdoor recreation

- Health and wellbeing

- Connection to nature

- Equality and diversity

- Technical report

Survey method

SPANS 2023-2024 used an online survey approach to provide robust coverage of the Scottish adult population aged 16 and over. To compile the data, twelve monthly survey waves were undertaken between April 2023 and March 2024, consisting of at least 1,000 survey completions per month.

Fieldwork was undertaken using the Prodege online consumer panel. Panel members go through a robust quality control process before they can join the panel and are then invited to take part in surveys in return for reward points.

Each month a sub-set of the Scottish panel was invited to take part in SPANS, targeted based on their demographics and place of residence. Sampling quotas were used to produce a representative distribution across gender, age, social grade and place of residence.

Questionnaire design involved a modular approach to ensure coverage of a wide range of topics of interest over the 12 survey waves. As such, while certain questions were included in every monthly wave, others were asked every other month, quarterly or less often.

Further details on the survey methods used are provided in the SPANS technical report.

Comparability with previous surveys

The online survey approach taken in 2023/24 differs from that used in previous waves of SPANS, where a face-to-face interviewing method was employed. This change of method was made for several reasons, including future-proofing the survey against declining response rates and rising costs of in-person surveying.

There can be small differences in the way people answer survey questions online as opposed to in-person. Variations in results between SPANS 2023/24 and previous waves (even when the wording of questions is kept consistent) may partly be influenced by methodological changes as well as changes in attitudes or behaviour at a population level. As a result, caution should be exercised when making comparisons with past SPANS results, and figures from the present survey should not be considered part of a continuous time series. SPANS 2023/24 forms a new baseline for comparisons with subsequent survey waves.

Further details on the potential impacts of these changes are provided in the SPANS technical report.

Health as motivation

Health and wellbeing are the most common motivations for spending time outdoors

To understand factors motivating people’s visits to the outdoors, those who had reported a visit in the previous month were asked to provide their reasons for taking that most recent visit. Following a qualitative analysis and categorisation of the reasons that were typed in, the following ten themes were mentioned most often:

- Exercise (mentioned in 26% of responses) – the most commonly mentioned reason for taking visits.

- Fresh air (25%) – a reason for taking visits in itself or alongside health and exercise reasons.

- Dog walking (8%) – while dogs were often taken on walks, the motivations given were more often related to personal health or other reasons.

- Enjoying nature (5%) – including appreciating scenery, wildlife, and the natural environment.

- Mental health (5%) – including benefits such as reducing anxiety and clearing the mind.

- Family and friends (1%) – spending quality time with family and friends.

- Relaxation (1%) – relaxation and unwinding were commonly mentioned alongside wider health and wellbeing related reasons.

- Fun (1%) – enjoyment and just having fun.

- Photography (2%) – taking photographs of nature, scenery, and wildlife.

- Escaping normal routine (2%) – generally escaping the daily routine and the hustle and bustle of modern life.

Health related factors emerge as strong influences on people’s decision to take visits outdoors, with exercise being the most frequently cited response. Other common reasons related to wellbeing, including relaxation and escaping the normal routine.

A selection of responses related to health or wellbeing are provided below:

“I do it because I enjoy it and its good exercise”

“Mainly for exercise and to get out of the house for a while.”

“Exercise, to get fresh air and to clear my mind.”

“Generally, I tend to get out to local parks via the local beach for mental health purposes.”

“I am rehabilitating after a broken leg earlier in the year, so building up my walking again. I can't manage hills yet, but walking on beaches is good exercise.”

“I retired last year from a job which required a lot of energy. I have to go out for exercise and nature. This is for my own health and wellbeing.”

“Mental wellbeing, fresh air and gentle exercise and bonding time with family members.”

“I love the outdoors, as do my family. My son is autistic and enjoys the freedom of being outside safe away from crowds.”

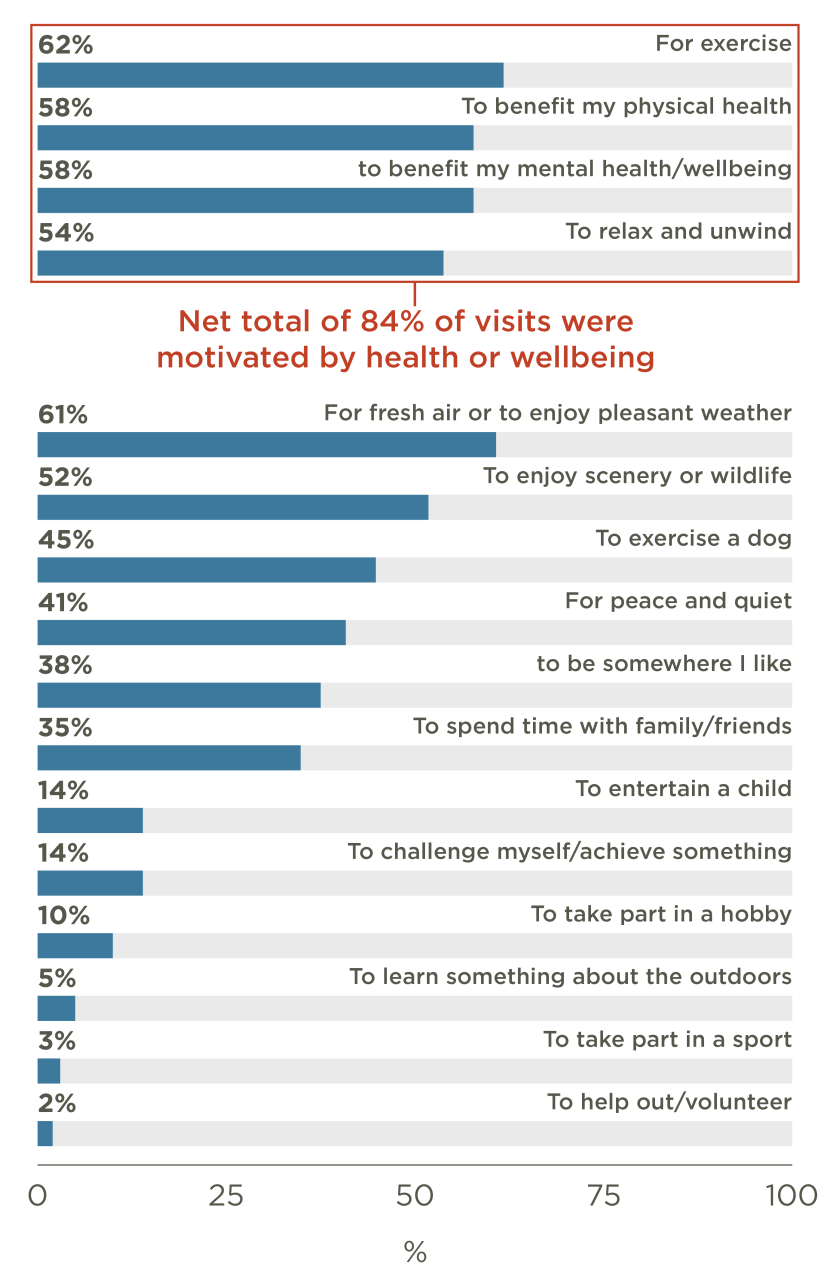

Following this open-ended question respondents were shown a list of potential reasons and asked to select those which best described their reasons for taking their most recent visit.

As shown in Figure 1, reflecting the reasons provided to the open-ended question, the most commonly selected motivations related to health and exercise with some 84% of visits taken for any reasons relating to exercise, physical health, mental health or relaxation. Note that as respondents often selected multiple reason for taking their visits (e.g. physical health and mental health), the sum of the percentages add up to more than 100%.

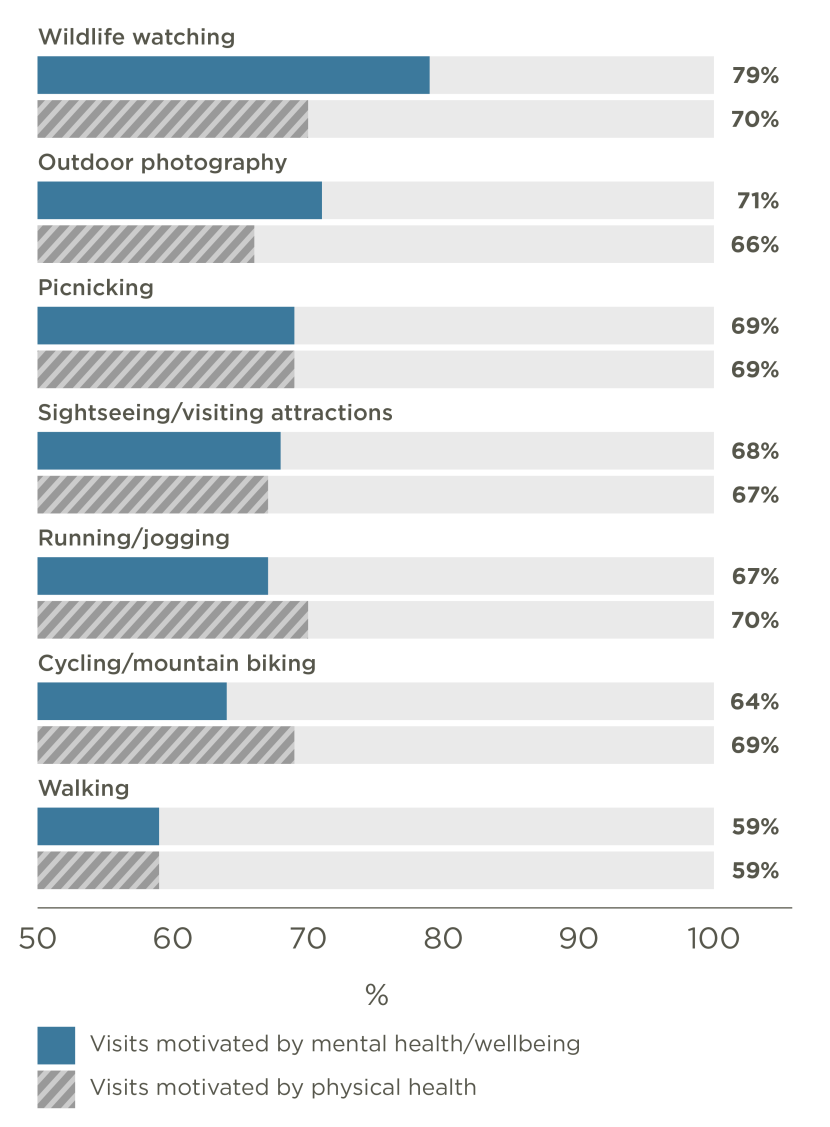

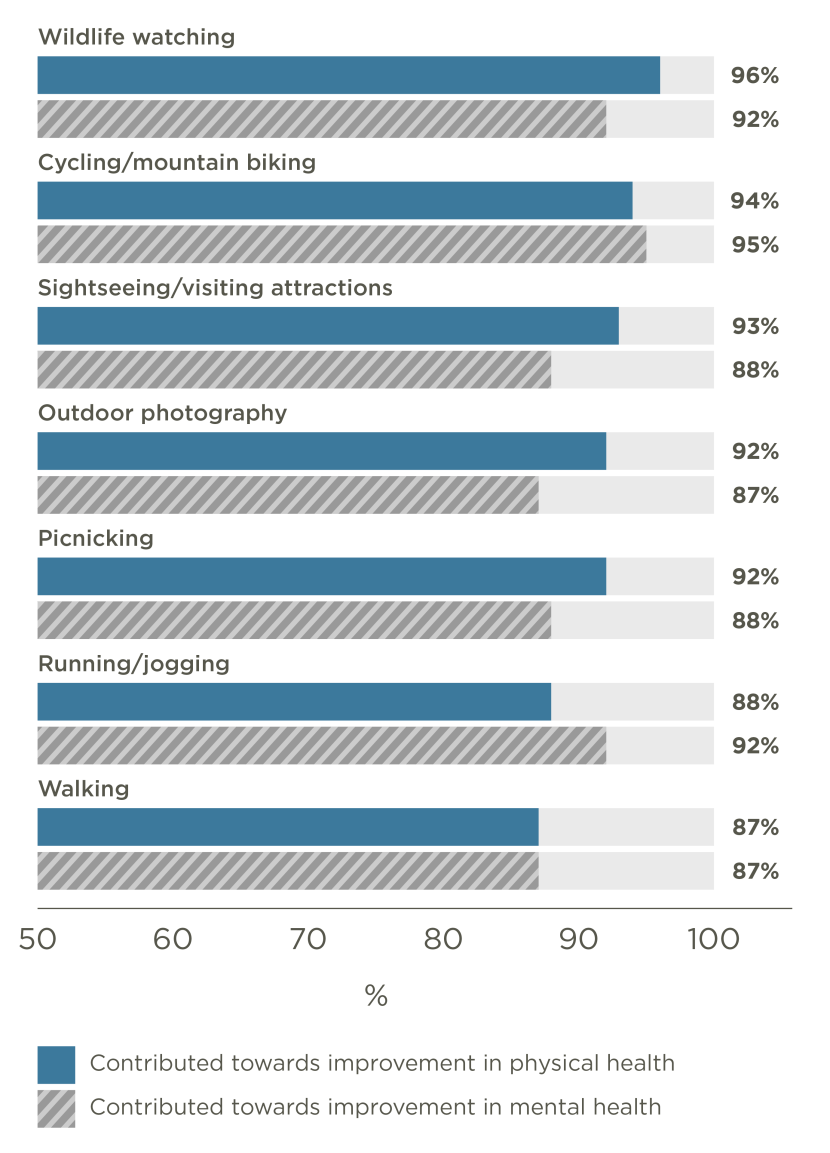

Some activities are more closely associated with mental than physical health benefits. Figure 2 compares the percentage of people stating that they were motivated by mental wellbeing or physical health benefits in relation to the activities undertaken on the visit. It is notable that these benefits are motivations for the majority of the visits taken for every activity.

Visits which included wildlife watching were more likely than those including other activities to be motivated by mental wellbeing benefits while those involving running or cycling were more likely than average to be motivated by physical health benefits.

Reported health benefits

People in Scotland recognise the mental and physical health benefits of outdoor recreation

In addition to being asked about their motivation for taking their most recent visit, people who visited the outdoors were also asked to rate the benefits they believed they had gained from the time they spent taking part in outdoor activities.

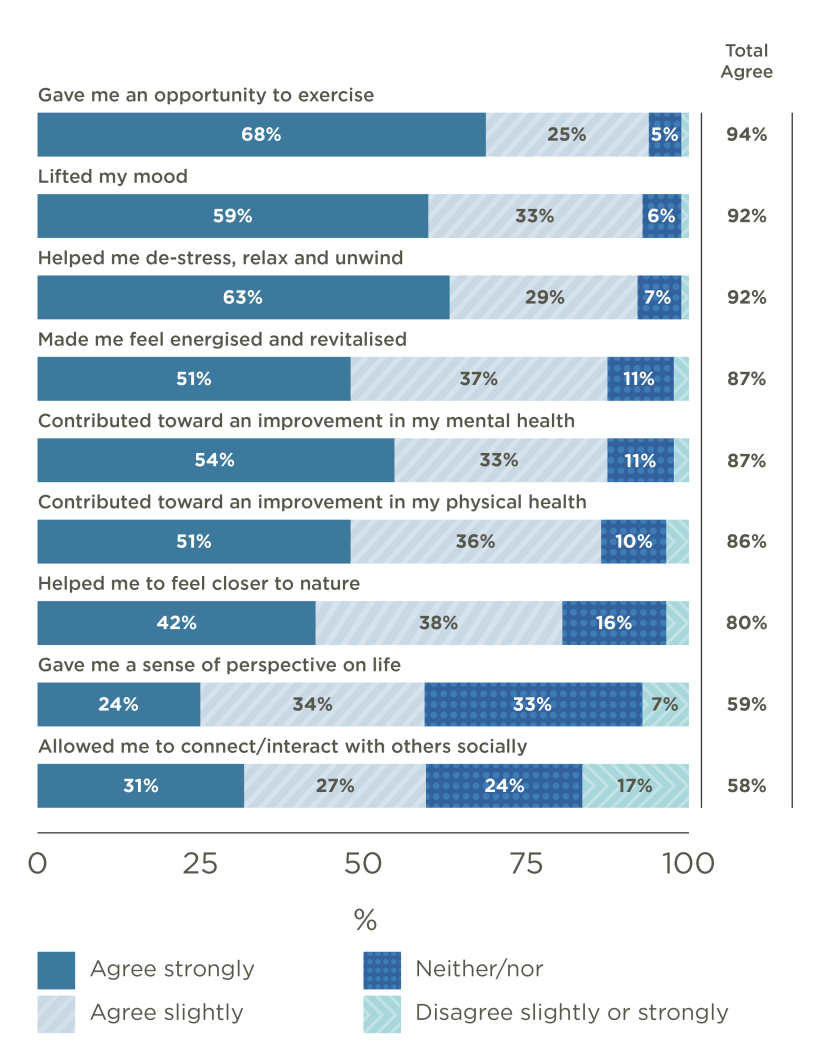

Almost all visits to the outdoors lift people’s mood and present an opportunity to exercise. As shown in Figure 3, the vast majority agreed with the statements relating to health and wellbeing, especially those relating to exercise, mood, and reducing stress.

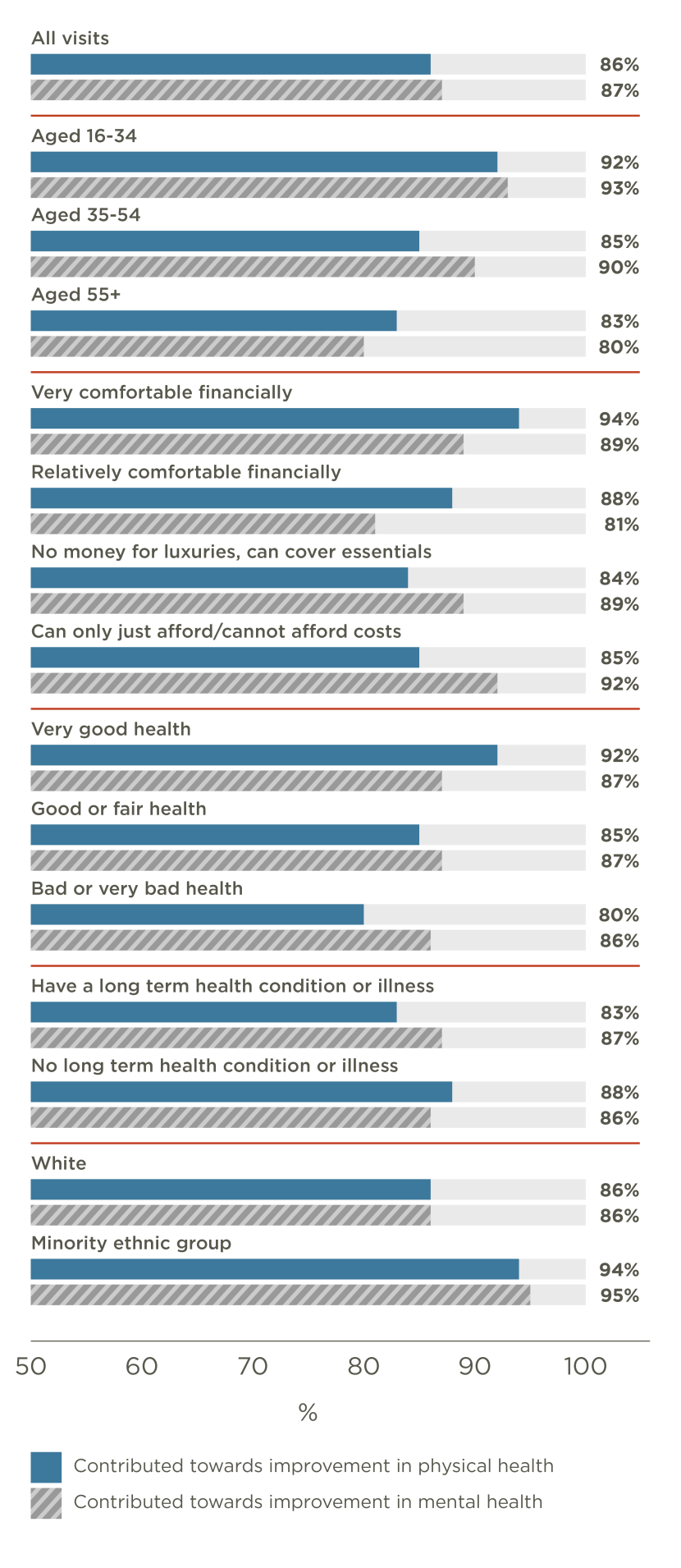

Overall, 87% of people agreed that their most recent visit contributed to an improvement in their mental health and 86% agreed that it contributed towards an improvement in their physical health.

Figure 4 shows the proportion of visits reported as beneficial to mental or physical health across different demographic groups. While people who were more financially comfortable were more likely to report physical health benefits, those who were less affluent reported the highest rates of mental health benefits.

People belonging to minority ethnic groups were more likely to report health benefits overall than white people. Similarly, younger people were more likely to report health benefits than older people.

The relationship between health status and physical health benefits is also notable, with those with good health or without long-term health issues more likely to report benefits.

While Figure 2, above, indicated that that mental and physical health were a motivating factor for people to participate in different activities, Figure 5 shows that the reported mental and physical health benefits of outdoor recreation also varied by activity. Some pursuits appear more closely associated with mental health, while others are more strongly linked to physical health.

At 96%, those taking part in wildlife watching were most likely to agree that the visit contributed to their mental health, while, at 95%, those taking part in cycling or mountain biking were the most likely to agree that the visit contributed to their physical health.

Visits taken for other reasons can provide ‘unplanned’ health and wellbeing benefits for the participant

While most visits seen as having provided health or wellbeing benefits were initially motivated, at least in part, by these potential benefits, in some cases the decision to visit the outdoors was driven by another purpose.

Specifically, 22% of visits seen as having contributed to mental health were initially taken for other reasons such as to enjoy pleasant weather or view wildlife. Similarly, 21% of visits seen as having contributed to physical health were taken for reasons other than exercise, such as walking a dog.

Physical health benefits

Outdoor recreation makes an important contribution to people’s overall physical activity

In addition to the questions concerning the benefits of health and wellbeing and their role in motivating visits to the outdoors, a further series of questions was included in SPANS with the aim of indirectly quantifying the health benefits of outdoor physical activity.

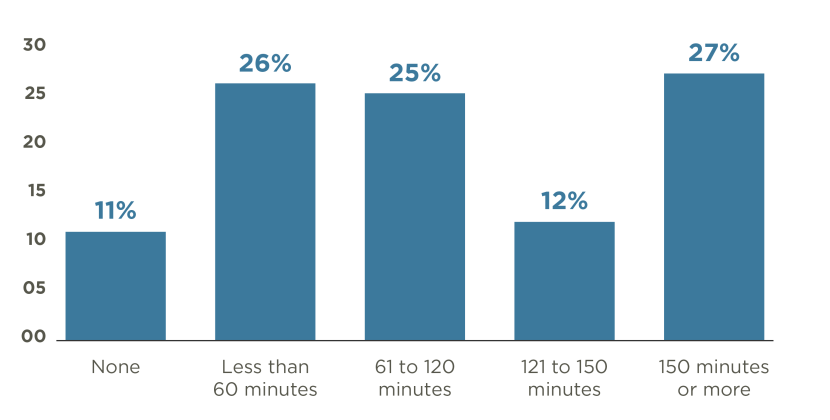

NHS physical activity guidelines indicate that adults should aim to undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity a week alongside strengthening activities that work all the major muscle groups. To determine the extent to which outdoor exercise contributes to this total among adults in Scotland, respondents were asked to estimate how many minutes of physical exercise they had undertaken at an intensity sufficient to make them fee warmer, breath harder, or make their heart beat faster (i.e. at a level considered to be moderate) while visiting the outdoors during the last week.

As illustrated in Figure 6, around a quarter of the population (27%) stated that they had undertaken this level of outdoor exercise for 150 minutes or more while visiting the outdoors, thereby meeting the NHS guideline target through outdoor activities.

A further 37% undertook this level of activity for between an hour and 150 minutes while a similar percentage undertook less than hour or no activity (37%).

The proportion of people undertaking 150 minutes or more of vigorous outdoor activities varied across population groups.

As shown in Table 1, nearly two-fifths of people reporting very good health (39%) indicated they reached this level, compared with less than a fifth of people reporting bad or very bad health (17%). Those without a long-term illness or health condition were also much more likely to reach this level (30% compared to 23% with a long-term illness or condition).

Table 1. Weekly participation in moderate physical exercise outdoors (150 minutes or more) by key demographic groups.

| - | % |

|---|---|

| Total population | 27% |

| Aged 16-34 | 23% |

| Aged 35-54 | 27% |

| Aged 55+ | 29% |

| Live in 10% least deprived areas | 27% |

| Live in 10% most deprived areas | 26% |

| Very comfortable financially | 24% |

| Relatively comfortable financially | 28% |

| No money for luxuries, can cover essentials | 27% |

| Can only just/ cannot afford costs | 25% |

| Very good health | 39% |

| Good or fair health | 25% |

| Bad or very bad health | 17% |

| Have a long-term illness or condition | 23% |

| Do not have a long-term illness or condition | 30% |

| White | 27% |

| Minority ethnic group | 18% |

| Own or look after a dog | 30% |

| Do not own or look after a dog | 25% |

BEN3: Overall, in the past week, how many minutes of physical exercise have you done in any outdoor environment, that is, activity which was enough to make you feel warmer, breathe harder and make your heart beat faster?

Base: Respondents surveyed in May or November 2023 (n=2,006). Demographic weight applied

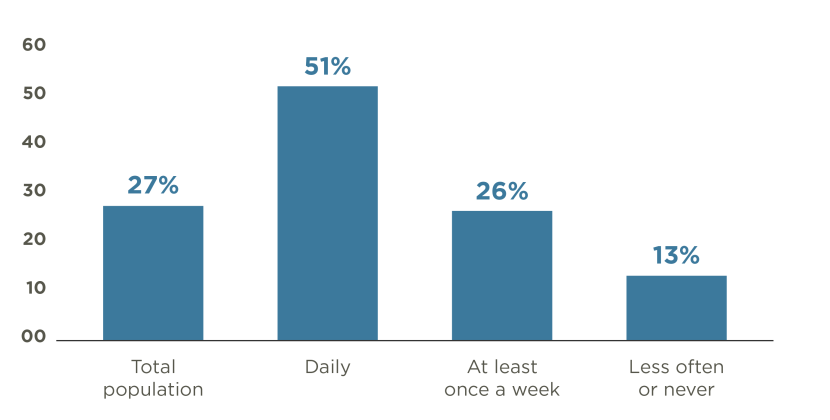

People who visited the outdoors most often were also most likely to contribute towards activity guidelines through participating in outdoor activities.

As shown in Figure 7, the proportion of adults undertaking 150 minutes or more of moderate exercise in outdoor places was significantly higher amongst those who visited the outdoors on a daily basis, while those who visited less than once a week were somewhat less likely to undertake this level of exercise outdoors.

Physical health benefits can come from a range of outdoor pursuits

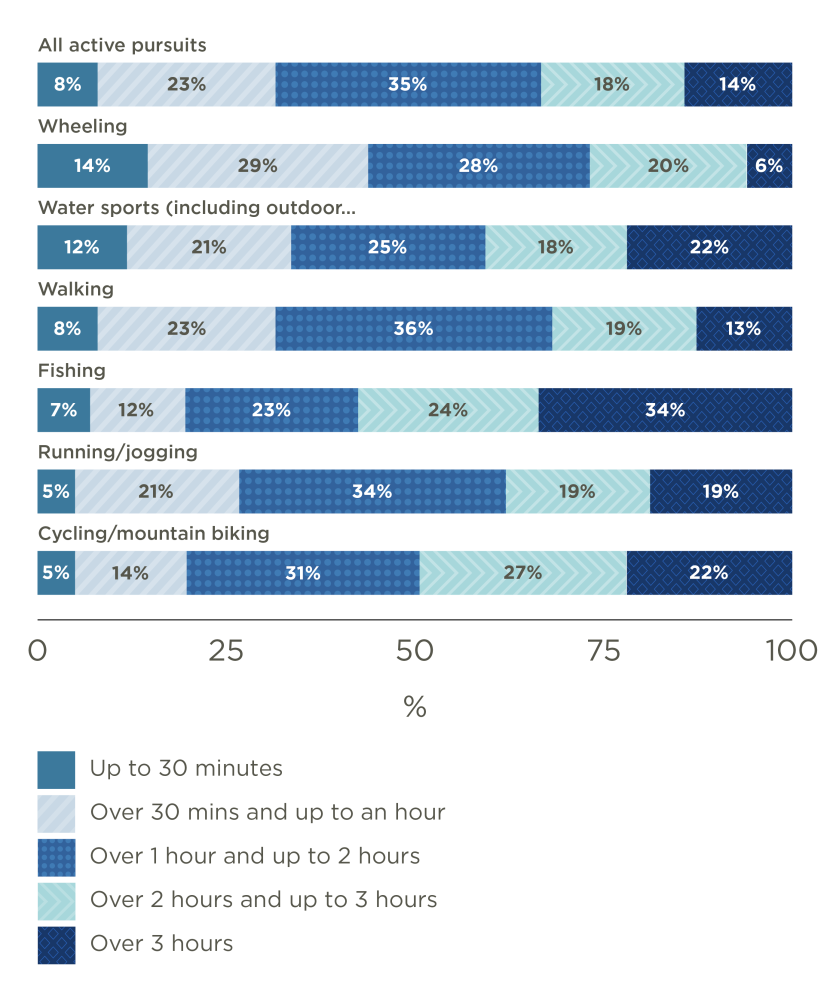

To further explore how outdoor recreation contributes to physical exercise targets, respondents were asked how long they had undertaken physical pursuits for during their most recent visit and whether this participation had been at an intensity that raised their breathing rate.

Visit duration varied considerably, though the shortest visits tended to be those involving walking or wheeling, while activities like running, cycling and fishing tended to be among the longest (see Figure 8).

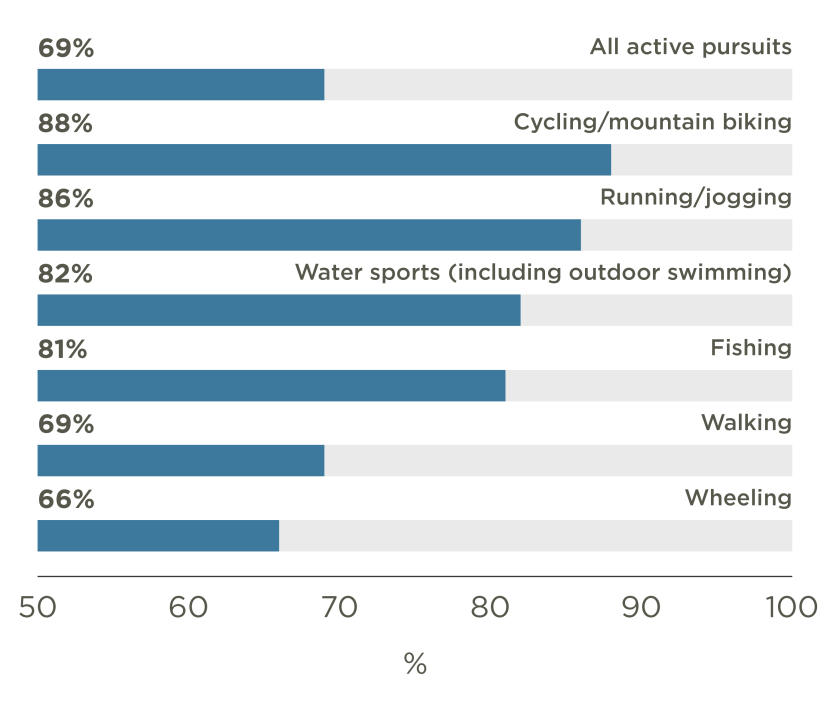

Overall, 69% of active pursuits involved a level of exertion sufficient to raise the participants breathing rate. This was most often the case when cycling, running, water sports or fishing were undertaken (Figure 9).

It should be noted that this elevated level of exertion could have been experienced at any point in the visit and potentially only for a short proportion of the total visit duration. For example, in visits including fishing this exertion level may have been during walking undertaken as part of the same trip (84% of fishing visits also included walking).

Mental wellbeing benefits

People who take part in outdoor recreation report higher levels of mental wellbeing

The Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales were developed to enable the measuring of mental wellbeing in the general population and the evaluation of projects, programmes and policies which aim to improve mental wellbeing.

SPANS included SWEMWBS, the shortened version of the scale, with all respondents asked to rate a series of 7 statements on a 5-point scale. These responses were then transformed into a single score which could be presented as an average across all respondents and amongst sub-sets of the survey sample.

Across the total SPANS sample the average SWEMWBS score was 22.1 (other UK wide national studies have found an average of 23.5 across the population).

Comparing SWEMWBS scores across people with differing frequencies of outdoor recreation (Table 2), those who visit the outdoors most often have the highest average scores, ranging from 22.7 amongst those who take visits every day to 21.6 amongst those who seldom or never take visits.

Table 2. SWEMWBS by frequency of outdoor recreation visits in last 12 months.

| - | Average SWEMWBS |

|---|---|

| Total population | 22.1 |

| Visit outdoors daily | 22.7 |

| Visit outdoors at least once a week | 22.4 |

| Visit outdoors less often or never | 21.6 |

Base: Respondents surveyed in May, July, September or November 2023 or January or March 2024 (n=5,806). Demographic weight applied

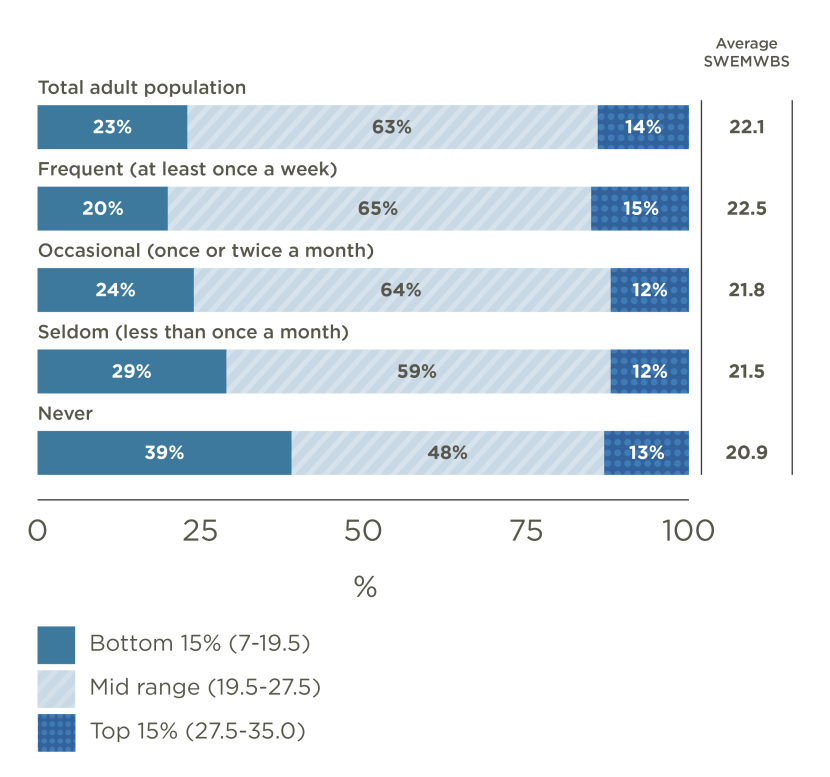

Categorising respondents into groups with low, medium, or high SWEMWBS scores (using a standard approach as described here), provides a further insight into the relationship between frequency of outdoor recreation and mental wellbeing (Figure 10).

While 23% of the total population are classified as having low mental wellbeing, this increases to 39% amongst those who never take part in outdoor recreation.

Greenspace and health

The role of local greenspaces

Local greenspaces are a vital resource of people’s physical and mental health

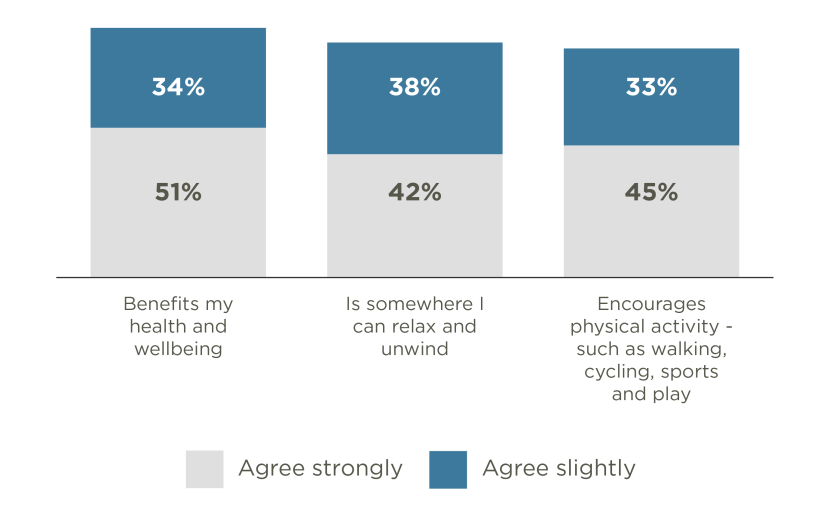

SPANS gathers a range of data on people’s use of, and attitudes towards, their local greenspace (see Outdoor Recreation report for the role of greenspace in outdoor recreation more widely). Figure 11 shows responses to statements relating to the health and wellbeing benefits of greenspace.

Most people acknowledge that their local greenspaces have a role in improving mental or physical health: 85% of people agreed strongly or slightly that local greenspaces benefitted their health and wellbeing, while 80% agreed that their local greenspaces were somewhere they could relax and unwind. 78% of people believed that their local greenspace encouraged them to take part in physical activity.

The extent to which people identified the health benefits of their local greenspaces varied depending on current health status. People in poor health were less likely (74%) to agree that their local greenspaces benefitted their health and wellbeing than those who rated their health as very good (91%). People who were satisfied with the quality of their local greenspace were also much more likely (96%) to agree that it benefitted their health and wellbeing than those who were dissatisfied (51%).

Further demonstrating the important role of local greenspaces in supporting physical health and mental wellbeing, Table 3 illustrates how those with easiest access to greenspaces and highest satisfaction levels were more likely to undertake 150 minutes or more of moderate intensity outdoor exercise per week.

Those who were very satisfied with their local greenspaces also recorded the highest average SWEMWBS scores.

Table 3. Percentage of population undertaking 150+ minutes moderate outdoor exercise and average SWEMWBS by proximity to, and quality of, local greenspace.

| - | % percentage undertaking 150 minutes+ moderate outdoor exercise per week | Average SWEMWBS |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 27% | 22.1 |

| 5 minute walk from local greenspace | 33% | 22.1 |

| 6-10 minute walk from local greenspace | 25% | 22.4 |

| 11-20 walk from local greenspace | 19% | 22.0 |

| Over 20 minutes walk from local greenspace | 20% | 21.9 |

| Very satisfied with quality of local greenspace | 35% | 23.3 |

| Quite satisfied with quality of local greenspace | 25% | 21.9 |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with quality of local greenspace | 20% | 20.6 |

| Quite or very dissatisfied with quality of local greenspace | 13% | 19.9 |

Base: Respondents surveyed in May, July, September or November 2023 or January or March 2024 (n=5,806). Demographic weight applied